Hi everyone. For the first time in my eight years with the organization, my board has decided to conduct a performance review. These are two words that send chills up and down every Executive Director’s spine, on par with “budget deficit” and “annual event.” The board had a clandestine meeting three weeks ago to talk about my performance as an ED. Soon they will meet with me to deliver feedback.

Hi everyone. For the first time in my eight years with the organization, my board has decided to conduct a performance review. These are two words that send chills up and down every Executive Director’s spine, on par with “budget deficit” and “annual event.” The board had a clandestine meeting three weeks ago to talk about my performance as an ED. Soon they will meet with me to deliver feedback.

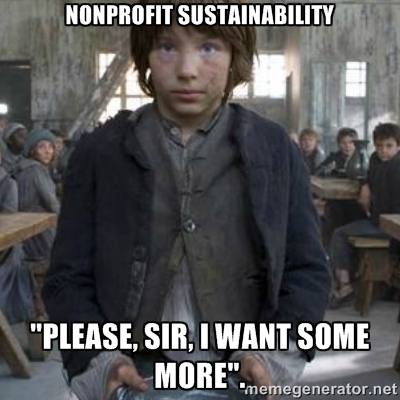

I’m nervous. I just know they’re going to say something like, “Vu, you’ve developed a reputation as a drunkard and a loudmouth. That’s affecting VFA’s image. We need you to stop mixing drinks at work. Also, funders are saying you’ve been dressing up as Oliver Twist during site visits and literally begging for money.”